Set to mediate Fla., Mich. issue

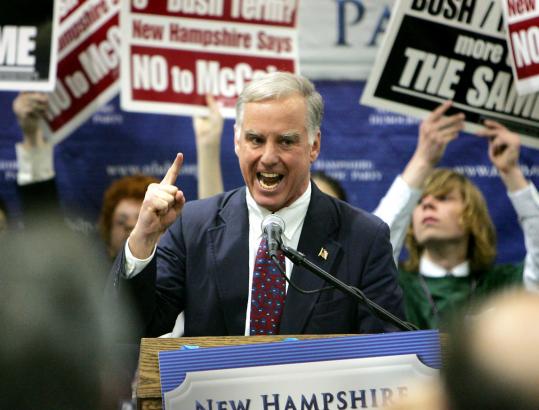

Howard Dean, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, in Manchester, N.H., last week. (Cheryl Senter/Associated Press)

Howard Dean, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, in Manchester, N.H., last week. (Cheryl Senter/Associated Press) MANCHESTER, N.H. - Howard Dean arrived at this month's New Hampshire Democratic Party convention with the purposeful brusqueness that has marked his years on the national stage, climbing out of his rental car with hardly a word for anyone before retreating into a holding area.

The chairman of the Democratic National Committee was there to deliver another of his famous red-meat speeches, exhorting the party faithful to evict the Republicans from the White House. But even amid the applause, there were signs of the Democratic Party's current discord in the room. Supporters of Hillary Clinton held up signs proclaiming: "Gov. Dean, count all the votes in Florida and Michigan!"

After the speech, Dean slipped out a back door and, disappointing a small crowd angling for a word or an autograph, strapped on his seat belt and left.

These are challenging days for Dean, the former family physician and Vermont governor who has run the national committee with a strong hand, helping his party win both houses of Congress during his 3 1/2 years as chairman. Now he finds himself in a familiar position - the center of a controversy - though in an unfamiliar role: peacemaker.

On Saturday, the DNC's Rules and Bylaws Committee will meet to decide whether to seat the delegations from Florida and Michigan at the party's August national convention in Denver. The two states were barred from representation because they moved their primaries ahead of a DNC-imposed timetable; but now their votes are crucial to Clinton's dwindling chances at the presidential nomination.

Whether Dean can broker a compromise and amicably resolve the Florida and Michigan crisis - and then stitch together his party after this year's bruising nomination battle - could go a long way toward determining who is the next president. Some are skeptical about his ability to finesse such a delicate, high-stakes situation.

"Howard's a doctor - doctors don't listen to people, they tell people what's going to happen, and that's part of the problem," said Garrison Nelson, a political scientist at the University of Vermont and a longtime critic of Dean. "That has always been Howard's style."

Even Joe Trippi, who managed Dean's 2004 presidential campaign, said Dean is usually better at taking charge than persuading.

"You come in the room, and he's pretty set on who should be the best guy at this, or where the party's money is going to go," he said.

But Trippi said Dean has surprised him this year.

"I think he's become a better mediator, a bit more conciliatory on this whole issue," he said.

Dean today is a more refined version of the presidential candidate of 2004, a man who relished blunt, off-the-cuff repartee with voters and reporters. (His "scream" speech after the 2004 Iowa caucuses is still the top video that comes up after a Google search of his name.) Even a few years ago, prudence was not his specialty.

"I hate the Republicans and everything they stand for," he said in 2005. Republicans, he also said back then, are "pretty much a white, Christian party."

Lately Dean has carefully contained his spontaneity, straining to avoid diverting attention away from Clinton and Barack Obama or to appear biased in the closely fought race. Earlier this month in New Hampshire, he read a large portion of his speech. On television, he often looks as if he is holding his breath; so sober was his recent "Tonight Show" appearance that the lively audience fell silent for long stretches.

David Berg, a close friend since their days as students at Yale, said Dean understands that his role has changed from insurgent to referee and party builder.

"I think he takes the job very seriously," he said. "He's not just being a political functionary, he actually thinks this grass-roots democracy is important to the future of this country."

State-party leaders backed Dean for chairman because he promised to rebuild the party from the grass roots up. In 2005, he dispatched a team to visit each state party and determine its needs, and the national committee then sent three to five new staff to each state to work on fund-raising, organizing, communications, or technology. Massachusetts, a state so blue that presidential candidates rarely campaign here in a general election, got four workers, as did Mississippi, a bastion of Bible Belt conservatism.

Public spats over the strategy erupted between Dean and Representative Rahm Emanuel, chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, who wanted every dollar for closely contested midterm races. Democratic strategist Paul Begala scoffed on CNN that Dean had hired people to "wander around Utah and Mississippi and pick their nose." Even after Democrats won big in the 2006 elections, James Carville, a Democratic strategist, called for Dean's resignation, declaring that the gains should have been greater.

But Democratic leaders outside Washington hail Dean's approach, calling it essential to the party's long-term success, and credit him with making a critical difference in the 2006 elections.

"Building a party that's in a difficult circumstance is a tough, tough job that's not something that can be done in six months to a year," said Don Fowler, a former DNC chairman from South Carolina.

Dean's strategy never looked better than it did earlier this month, when Democrat Travis Childers won a special congressional election in a conservative Mississippi district. Because of Dean, the Mississippi state party was prepared to help, including Terry Cassreino, a veteran Mississippi political columnist who became the state party's communications director.

"They didn't have anything back when I was covering the capitol, politics, and government," Cassreino said. "They had maybe one staff person, and the Republican Party had a full staff. This obviously gives us a chance to compete."

Dean has withstood even harsher criticism for his handling of Florida and Michigan. He appears to have taken a hands-off approach to the Rules and Bylaws Committee's initial decision to punish the states by stripping them of their delegates, but once it was made, he supported it.

Despite the urging of the national committee, the states did not hold alternative nominating contests. Whether this was a result of Dean's diplomatic shortcomings or the state party leaders' stubbornness is unclear. Karen Thurman, chairwoman of the Florida Democratic Party, said Dean became more personally engaged this spring but before that left most of the negotiations to national committee staff and rules committee leaders, who, she said, came up with no feasible alternatives.

"I don't think he wanted this to happen to Florida, but I think he was also pretty dug-in about the rules," she said, adding that she and Dean see eye to eye on most other issues.

But James Roosevelt Jr., cochairman of the rules committee, said Dean worked quietly but intensively to try to resolve the dispute, and that he and DNC representatives labored for days on end to devise alternatives and to find ways to fund them. "Howard believed he could be most effective trying to work behind the scenes," he said.

Some say the dispute may jeopardize the Democrats' ability to compete in two important states. Kenneth M. Curtis, a former governor of Maine who was chairman of the DNC in the late 1970s and is now a superdelegate living in Florida, said Dean should "step down and let somebody new come in who wasn't tainted by this whole mess."

Dean has no intention of doing that. But much is riding on his ability to help broker a compromise this weekend. All he has to do is come up with a solution that will satisfy two scofflaw states, two warring campaigns, and a few million people who want their votes to count - without a Democratic president in the White House to back him up.

James Blanchard, a former Michigan governor and cochairman of Clinton's campaign in his state, said, "I trust Howard Dean to get this worked out."![]()

No comments:

Post a Comment